|

|

Monday, November 20, 2006

|

|

When Ryan Mottesheard met Kim Ki-Duk

|

When Ryan Mottesheard met Kim Ki-Duk

When I met Kim Ki-Duk to talk about his new film "Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring" I didn't quite expect him to be so... well, normal. I don't know what exactly I expected of the Korean enfant terrible, but after seeing his movies, I didn't think it would be the soft-spoken, courteous, humble, youthful-looking gentleman who sat across from me and thanked me for being familiar with his earlier work (as if I was doing him a favor). After all, this is a guy who, with 2001's "Bad Guy," raised the ire of feminist critics in his native Korea with his sympathetic portrait of a pimp who enslaves a young student into prostitution. The same guy whose international breakthrough, "The Isle," concerns a murderer, a mute woman, and some very interesting uses for fish hooks.

But then, there's nothing predictable about Kim. When he, very reluctantly, talks about movies, he offers that he feels the most kinship with American doc-shock jock Michael Moore, despite the fact that Kim's subtle, abstract films about modern-day Koreans who lives on society's fringes is (to me anyway) the polar opposite of Moore's sledgehammer technique. Maybe it's Moore's blue-collar background that Kim admires, as Kim himself tends to flaunt his lack of formal education on his sleeve. A high-school dropout, Kim worked in factories from the ages of 16-20, then spent five years in the Korean military before moving to France to peddle his paintings on the streets. Only after returning to Seoul did he think about film as a career and even then, it was with an autodidacticism that more closely recalls silent-era pioneers of a hundred years ago than the media-saturated generation that he belongs to.

In any case, Kim's latest, "Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring" (which opens today from Sony Pictures Classics), represents a huge step forward in Kim\'s body of work. While not entirely abandoning his earlier visual and thematic preoccupations, "Spring, Summer..." is more transcendent, it stays with you longer. Much of this has to do with its stunning formal beauty. But it also has to do with the fact that Kim he has moved beyond the facile sex-and-violence Molotov that he, at times, has used as a crutch.

indieWIRE spoke with Kim about moving into new territory, his controversial past films, and his place in the current red-hot Korean film industry.

indieWIRE: "Spring, Summer..." is widely seen as a departure for you, or at least the beginning of a new stage in your career. Would you agree with this?

Kim Ki-duk: I agree that this film is different. In my other films there has been a lot of brutality and cruelty and anger inside them. But with "Spring, Summer...," I also wanted to show the healing powers of forgiveness and tolerance.

iW: What made you move in that direction?

Kim: I don't know. I think that's the important thing, that I have no idea. When I first visited Jusan Pond (the setting for "Spring, Summer..."), I scratched out a few ideas on paper. But I made this film without a script.

iW: Location is very important in all of your films and here it's the floating monastery on Juson Pond. How did you find this place or did you already know it and devise a story around it?

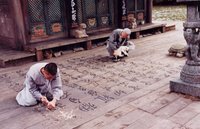

Kim: Initially, I didn't imagine a floating temple on the water and had never seen one. At first I wanted to build a temple in the mountains, but I was unable to find a suitable place. I kept thinking of a way around this and then finally, I happened upon Juson Pond. Korea has lots of beautiful scenery but Juson Pond is a very unique place since it has 300-year-old trees growing out of the water. And I felt like this would be an interesting challenge, to build a floating temple, which was built from scratch.

iW: Is the temple still there?

Kim: No, it was destroyed. But I hope it still exists in people's minds after seeing the movie.

iW: What relationship do you think a specific location plays within your films?

Kim: I think that location and space are the most important aspect of all of my films. Only after finding a location do I think about the story or about casting an actor. I travel all over Korea to find a particular place and then once I find it, I go about making my film.

iW: You've often been labeled a provocateur or an enfant terrible. What do you think of these claims?

Kim: I understand why people call me a provocateur, but I think this is simply because they see me as an outsider. If they really look at me and my films, they can see that there's something more than that. I am very interested in human beings and I always try to look at diverse human beings with a different perspective. If people really look, they can see my other ideas.

iW: Yet several of your earlier films have been quite controversial, "Bad Guy" in particular. Have you ever consciously courted controversy?

Kim: I never tried to be controversial. My films have been called provocative but I never meant to be. In the case of "Bad Guy," it wasn't controversial at all for me. I just made the film in as honest a way as I knew how. In "Bad Guy," I wanted to examine this character (a mute, violent pimp) and try and figure out if he is really bad or not. If people accept that there are people out there like "The Bad Guy" then they'll understand the movie. But people who have very strict ideas of morality will hate the film.

iW: You quit giving interviews for a while after the hostile reaction of "Bad Guy" by the Korean press. What is the difference between the Korean audience reaction to your films and the international audience?

Kim: European audiences tend to really like "Bad Guy" and they're not as offended by it as the Korean people were. But the interesting thing in Korea is that female audiences liked the film much more than male audiences, I think because males see themselves in the main character.

iW: How has "Spring, Summer..." been received in Korea?

Kim: I've never had really wide success in Korea. "Spring, Summer..." drew 150,000 spectators (recent Korean blockbuster "Silmido" recently topped 10 million spectators) and my latest film "Samaria" has already drawn 200,000. But I don't think it's really important how many people watch "Spring, Summer...," but rather, WHO watches it. I would rather have fewer people see it and understand it than more people watch without understanding it. Also, I find it interesting that Korean people will see one of my films and get hooked on watching them, despite the fact that they don't like them.

iW: As your films have gotten more well-known, has the broader international audience affected your filmmaking style?

Kim: This is my tenth film but from the beginning, I never thought of my films as "Korean films." I've always had an orientation toward international film, and probably because of this I've been able to develop an international reputation faster than other Korean filmmakers.

iW: The cinema isn't the most logical place for you to have wound up considering your background, as a factory worker and a soldier. What was it that initially drew you to cinema?

Kim: I just woke up one day and realized I would be a filmmaker. It's ironic, but I was able to become a filmmaker specifically because I never had a film education. There are so many people who study so hard to become film directors and maybe this is why they're unable to actually do it. I think a director is someone who films life and the biggest obstacle for film students is that they waste too much studying films and not enough studying life.

iW: Korean cinema has received quite a lot of attention in the last few years, both at home and abroad. Do you feel a certain kinship with any of you contemporaries such as say Chan-wook Park ("JSA," "Old Boy"",1] or Sun-woo Jang ("Lies")?

Kim: I'm very different from those two filmmakers. Maybe at the beginning of my career I was somewhat more involved in that movement, but now, I don't really feel any kinship with other Korean films that are being made.

iW: Why then do you think there has been this resurgence in Korean cinema then? Shucking the global trend, in 2003, eight of the top 10 top grossing films in Korea were domestic films.

Kim: I think there are two main reasons. Firstly, Korea has a long history of government regulation and censorship so we couldn't explore certain subject matters. That was always an obstacle. But now, everything has changed and directors can freely express themselves by making their own unique films. And secondly, Korea has lots of students who have studied film. It's quite a boom right now. But I don't think that Korean cinema is the best cinema in the world... at least not yet. Most of it just copies trends and styles of Hollywood film. Maybe there are one or two directors out there who making a new style of Korean film such as Lee Chang-Dong (2002's "Oasis").

iW: I've read that you have expressed interest in working in Hollywood. Is this true?

Kim: (laughs) Yes, I actually said I would like to remake "Bad Guy" in Hollywood with Brad Pitt as the lead. But I don't think Hollywood is very interested in this idea. I don't really understand why Hollywood studios buy remake rights to Korean films. If they like the film in the first place, why don't they just distribute the Korean version? |

|

posted by santhosheditor

8:06 PM

|

| |

|

-

-

good...

collect these type of items and post...

it is informative

|

|

| << HOME |

|

|

|

|

|

|

myprofile |

previouspost |

myarchives |

mylinks |

bloginfo |

|

very nice interview